In a 2009 trip to Chile, high in the Altiplano (high plains) region of the Andes, I saw my first vicuñas, guanacos, rheas, and three species of flamingo. Like Charles Darwin and many naturalists and biologists since, I was struck by their close resemblance to camels, ostriches and flamingos, respectively, of Africa and the Middle East. How did they get there? Where did their ancestors come from? What combination of continental drift, climate change and the animals’ dispersal ability could have caused such odd, disjunct distributions?

Everyone who has read even a little about South America’s biodiversity knows about the collection of very strange, extinct mammals with no relatives anywhere else, whose ancestors were presumably in the part of Gondwana that would become South America when it split from Africa about 110 MYA; and about the Great Biotic Interchange occasioned by the closure of the Isthmus of Panama about 3.5 MYA, allowing a flood of North American species to enter South America, and vice versa. But relatively little has been written about the species that managed to populate the “island” continent during the 100 million years or so that it was not connected to any other land mass.

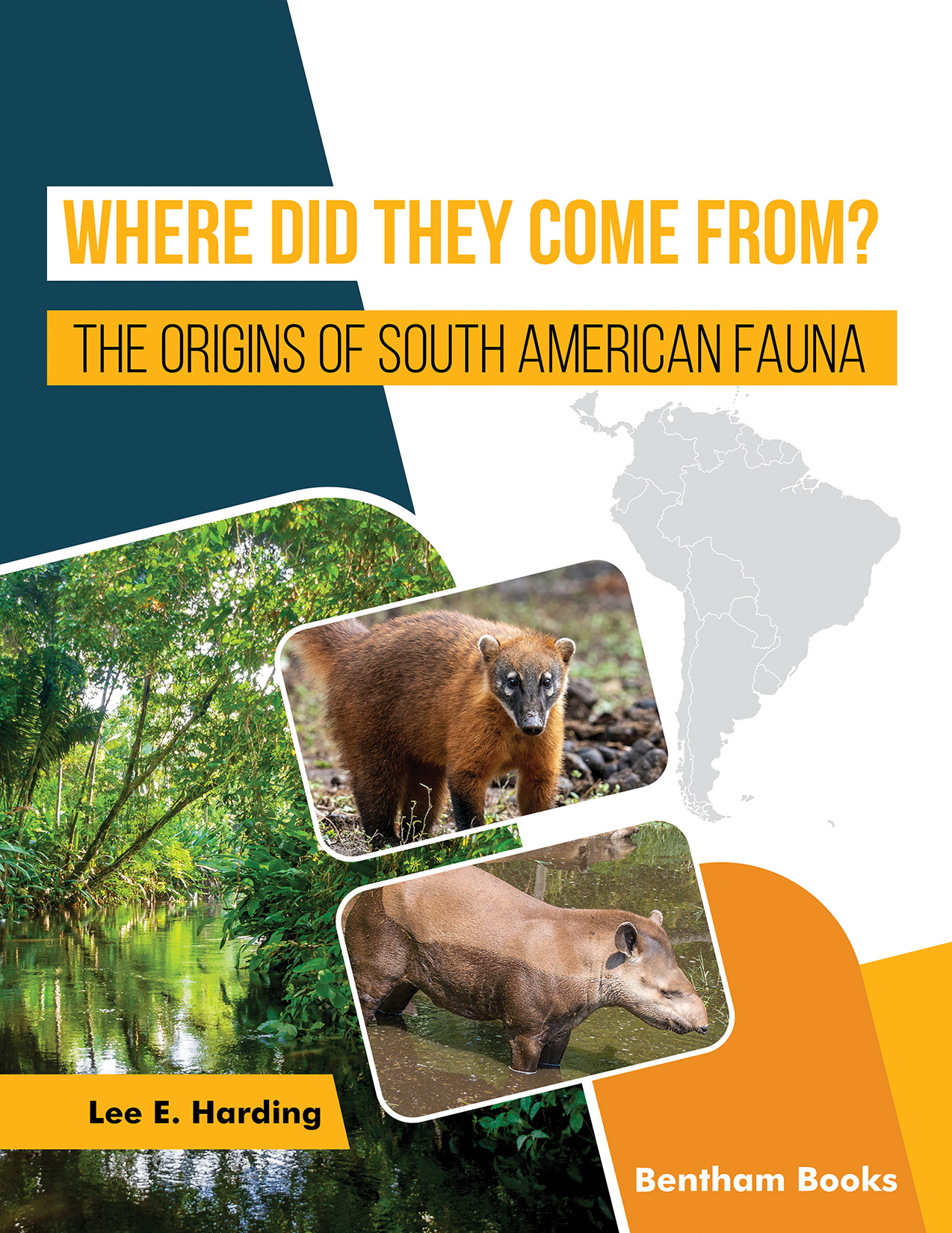

Considering these questions, more appeared: How did the five species of tapir, all in the same genus, come to be distributed in Southeast Asia and South America and nowhere between? Why do two members of the weasel family—Galactis, grison, two species and Lyncodon, Patagonian weasel—occur in South America when their closest relatives, zorillas (Ictonyx), are only in Africa? Besides flamingos, why do some genera of unrelated birds, such as jacanas, painted snipe, thick-knees and dippers, have only a handful of species worldwide with one or two in South America and the others scattered across Africa, Eurasia and/or Asia?

The temporal scope of this enquiry is the late Cretaceous era starting about 110 MYA through the Cenozoic (starting 66 MYA) to the late Pliocene (3.5 MYA). This is the period that South America was essentially an island continent, isolated from other land masses. However, land bridges or island chains persisted among Australasia, Antarctica and South America for the first half of this period, more or less, depending on the sea levels relative to islands and coastal plains. When Antarctica became glaciated, approximately 30 MYA, these connections were severed by ice for terrestrial biota. Since no story about South America’s biodiversity would be complete without at least mention of the Great Biotic Interchange, initiated with the closure of the Isthmus of Panama around 3.5 MYA, I include a brief review of the animals that immigrated subsequently.

Geographically, the scope is South America. Other land areas are mentioned to the extent that they may be sources of South American biota or recipients of lineages that evolved within South America and emigrated.

South America has a fauna that elicits superlatives in every sphere. It has the largest beetle on the planet, the longest snake (Anaconda), the largest rodent (capybara), the smallest and largest species of hummingbirds, the mightiest freshwater fish and the smallest and largest anurans (frogs). It has the Andean condor, the most majestic of flying birds. No other tropical region rivals the magnificence of the diversity in form and colour of the butterflies and birds of the Neotropical rainforest.

Part 1 is about how South America came to be: its separation from Africa and Laurasia (including what would become North America) about 110 MYA, its separation from Antarctica and its subsequent glaciation about 30 MYA, and finally the connection to North America. Both plate tectonics and volcanism were involved in the final connection to North America, with filter pathways for north-south dispersal in the Caribbean and the Isthmus of Panama. During its long isolation, changing global temperatures and sea levels assisted dispersal across what are now oceans. I comment on mechanisms of trans-oceanic dispersal and conclude Part 1 with a mention of some of the earliest biological explorers. In Part 2, the creation of the main geographic and ecological features of South America is reviewed. Part 3 is about the plants and animals whose ancestors were in South America at the time of its separation from Africa and their lineages that evolved within the isolated continent. In a sense, the modern descendants of these ancient lineages are “native”: neither they nor their ancestors came from somewhere else. Part 4 introduces “exotic” species, or taxonomic groups (“taxa”, for short), whose ancestors managed to reach South America during its long isolation and then evolved and diversified there. Part 5 summarizes the latest wave of new arrivals: those whose ancestors invaded South America from North America as part of the Great Biotic Interchange, after the connection with North America. This wave continues today. In Part 6 we consider research questions for the future.

Lee E. Harding

Retired from the Canadian Wildlife Service

Coquitlam, British Columbia V3J 6Y3

Canada